Concurrency and parallelism are orthogonal

The best way to learn concurrency that I've found so far is by reading these two resources:

- This glossary of concurrency terms by Reinis Ivanovs (slikts) (slikts, 2025)

- The article "Programming Paradigms for Dummies" by Peter Van Roy (Van Roy, Peter, 2012)

Here are the main points that were new to me and helped me sort out the mess in my head:

- A synonym for the concept of concurrency is independence

- Concurrency is not about how tasks are executed (e.g. using preemption, time slicing, etc.), but parallelism is

- Rather, concurrency (independence) is about the degree of dependency between tasks

- The opposite of concurrent is sequential (completely dependent tasks)

- The opposite of parallel is serial

- Concurrency and parallelism are completely orthogonal

In this post I'll vent about my frustrating experience of learning concurrency (which I dare to guess is pretty common), and try to guide you through the linked resources.

My frustrating experience of learning concurrency

At some point in my journey of learning programming

I had to learn the concept of concurrency.

As programmers often do,

I started by googling for

a quick tutorial on Python's threading library

and reading the explanations of concurrency

like the ones in this Stack Overflow thread.

I had a difficult time figuring it out. What is the relationship between concurrency and parallelism? How is it related to threads and processes? Is concurrency about preemption and time scheduling? The more I read different explanations, definitions, and analogies, the more confused I was.

Then I randomly stumbled upon a glossary of concurrency terms (slikts, 2025) and found it absolutely enlightening. It had cleared up the mess in my head and I could finally answer all those questions.

The biggest issue that makes figuring out concurrency difficult is that there are quite a few different meanings of "concurrency" floating around in the programming community.

Consider that each meaning can be formulated in many ways, that the explanations can approach from many different angles, and that the analogies for the fundamentally different meanings sound very similar to each other. Thus, an unsuspecting beginner is doomed to try to make sense of similar but contradicting explanations because, unbeknownst to him, they were explaining fundamentally different things.

The third issue is that the term "concurrency" itself is an unfortunate one. According to the dictionary, "concurrent" is basically a synonym for "parallel", which is not at all the case for the programming concept of concurrency.

A wrong understanding concurrency

My previous (WRONG) understanding of concurrency went something like this:

- Parallelism is when you literally execute more than one task at the same time (e.g. on multiple cores of a processor)

- Concurrency is when you execute tasks such that they appear to be executed at the same time, while not necessarily being executed in parallel (e.g. on a single core);

Clearly, by this definition, concurrency can be seen as a union of two techniques:

- parallel execution

- time slicing (preemption)

This led me to reason that concurrency implies parallelism but not vice versa, i.e. that concurrency is a more general description of the method of execution, whereas parallelism is a more specific description of the method of execution.1

This understanding of concurrency seems to be quite popular, judging by the fact that it is the top answer in a StackOverflow thread with over 1.8k upvotes, despite being misleading.

A better definition of concurrency

Join me now, then, for an eye-opening definition of concurrency presented in The Glossary:

Concurrency is about independent computations that can be executed in an arbitrary order with the same outcome. The opposite of concurrent is sequential, meaning that sequential computations depend on being executed step-by-step to produce correct results.

Ahhh, like a breath of fresh air!

Right off the bat, notice that in this definition, concurrency has an entirely different essence: it is not about how you execute tasks, it is about the tasks themselves. In other words, it is not a technique, or a description of a technique, rather, it is property of tasks in relation to one another.

Thus, it is incorrect to say "executing tasks concurrently". Instead, we talk about "factoring a program into concurrent modules", or simply "concurrent programming".

Pay attention to the key term "independent" – it is actually defined as a synonym for "concurrent"! 2 That is awesome, because "independent tasks" makes much more intuitive sense than "concurrent tasks".

Note however that concurrent tasks are almost never completely independent, instead they have some dependencies between each other. One example of a dependency is when a task needs to wait for a result from another task to be able to continue. Exercise for the reader: try to figure out what is the fundamental nature of dependencies between tasks.

When the interaction between interdependent tasks is well-defined in the model, it is called communication 4. The two most popular paradigms for communication are shared memory and message passing. They don't restrict the programmer, which means you have the freedom to do anything you want. But this freedom comes at a cost: it's very hard to verify that your programs don't contain bugs like data races. There exist more restrictive paradigms (e.g. CSP, FRP) that make it impossible to have such bugs, and we should strive to use such paradigms whenever possible. For more on this, read Van Roy's article.

Quick note: Most commonly (I think), when we speak of concurrency, we imagine OS threads, but there are many other things that can be concurrent: coroutines, processes, actors, etc. What umbrella term can we use to capture all these units of concurrency? Van Roy uses the term "parts", as in "parts of program code". The Glossary uses the term "unit of concurrency", which is a bit long, but more frequently it uses "computation", which I like more because it's more general (for example, it also applies to the execution of code generated dynamically), and because in SICP they also talk about "computational processes" as the fundamental concept of a running program. So I think "computation" and "computational process" are the best terms to use to talk about "units of concurrency". The more colloquial term "task" is probably also fine because it doesn't have other implementation-specific meanings (unlike the term "thread" for example).

Now look at this:

Concurrent programming means factoring a program into independent modules or units of concurrency.

I think we should avoid saying "execute X and Y concurrently" and instead say "write a concurrent program that does X and Y" to emphasize that "concurrency" is a property of tasks, not a technique.

Now let's continue to parallelism:

Parallelism refers to executing multiple computations at the same time, while serial execution is one-at-a-time. Parallelization and serialization refer to composing computations either in parallel or serially.

The colloquial meanings of "concurrent" and "parallel" are largely synonymous, which is a source of significant confusion that extends even to computer science literature, where concurrency may be misleadingly described in terms that imply or explicitly refer to overlapping lifetimes.

I love it when after long hours of frustration I stumble upon an article that acknowledges that there is confusion out there and proceeds to sort things out.

Van Roy's article delivers the final blow to put an end to all confusion:

Concurrency and parallelism are orthogonal: it is possible to run concurrent programs on a single processor (using preemptive scheduling and time slices) and to run sequential programs on multiple processors (by parallelizing the calculations).

So there you go, my old ideas about concurrency implying parallelism got knocked out the window, and in its place a beautiful model emerged, shining with abstract purity and generality.

| Sequential tasks | Concurrent tasks | |

|---|---|---|

| Serial execution | regular programming | time slicing on a single processor |

| Parallel execution | SIMD | threads running in parallel |

Analyzing misleading definitions from the web

Although the new definition of concurrency is fundamentally different, you can see how most other definitions follow from it. Let's see a few:

Concurrency is when two or more tasks can start, run, and complete in overlapping time periods – Top answer on StackOverflow

I believe this definition is equivalent to the one from The Glossary. Indeed, if two tasks are independent and can be run in any order, then it follows that they can be sliced and interleaved using the time slicing technique.

However, you can see how it hints heavily at the idea of time slicing, which might confuse some to believe that concurrency is about time slicing, whereas in fact the two ideas are orthogonal. Which is why I don't like it as an introductory definition of concurrency. I think the relation between concurrency and the technique of time slicing is better made explicit through a statement like this: "Concurrent tasks can be executed seemingly in parallel using the technique of time slicing".

Also, I think it doesn't extend well to capture the idea of partially interdependent tasks.

Here is another one from the same Stack Overflow thread, but written as a comment to the question, which didn't stop it from getting 450 upvotes:

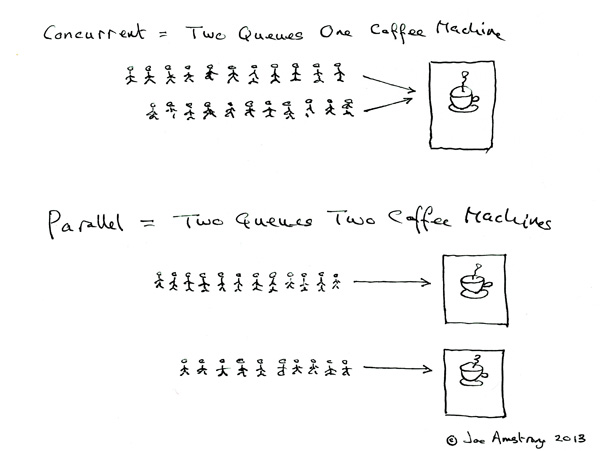

short answer: Concurrency is two lines of customers ordering from a single cashier (lines take turns ordering); Parallelism is two lines of customers ordering from two cashiers (each line gets its own cashier). – Comment on the same SO question

This analogy doesn't explain concurrency, it explains time slicing. Replace the word "concurrent" with "serial, but using time slicing", and the analogy becomes correct.

Again, concurrency and time slicing certainly are good friends and often go hand in hand. But if we want to avoid confusion, we must be rigorous about what is what.

Interestingly, this analogy was presented on Joe Armstrong's blog, one of the fathers of Erlang, a language that is primarily about concurrency. Granted, it did generate quite a heated conversation, which might have been Armstrong's goal with this post.

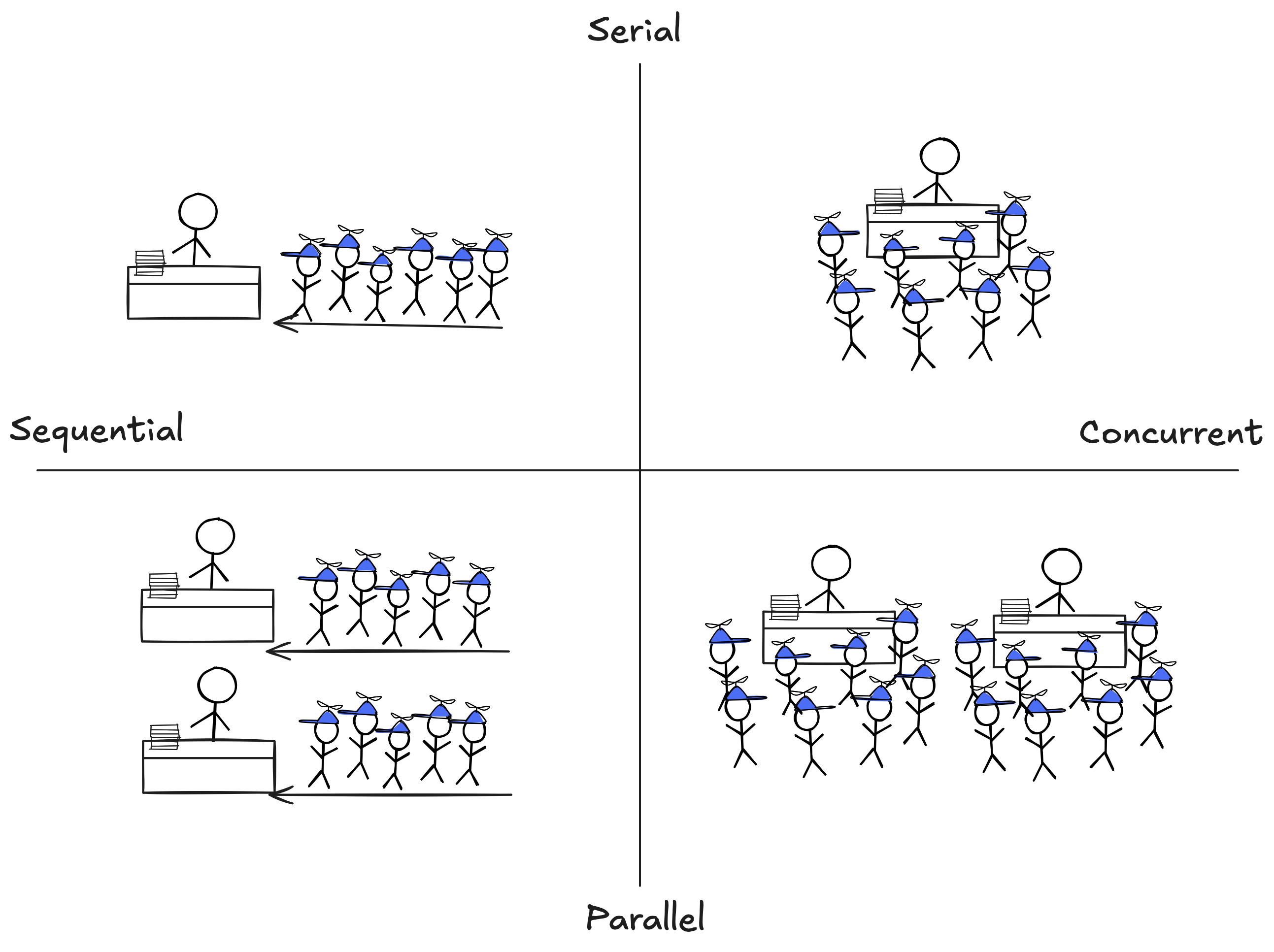

An improvement on this analogy would be to present people in an unordered crowd rather than in a queue, as I've tried doing here:

It represents concurrency without parallelism with kids crowded around a table for autographs: it doesn't matter in what order they go, so they are independent, and the celebrity can only sign one autograph at a time, so it's serial. To add parallelism, we simply create a clone of the celebrity.

However, this analogy is not perfect either. What in this analogy is telling us that the kids standing in the queue are actually interdependent? Logically speaking, it doesn't matter in what order the kids will get their autographs, so they are still independent, even though they are standing in a queue5.

My tutorial on concurrency

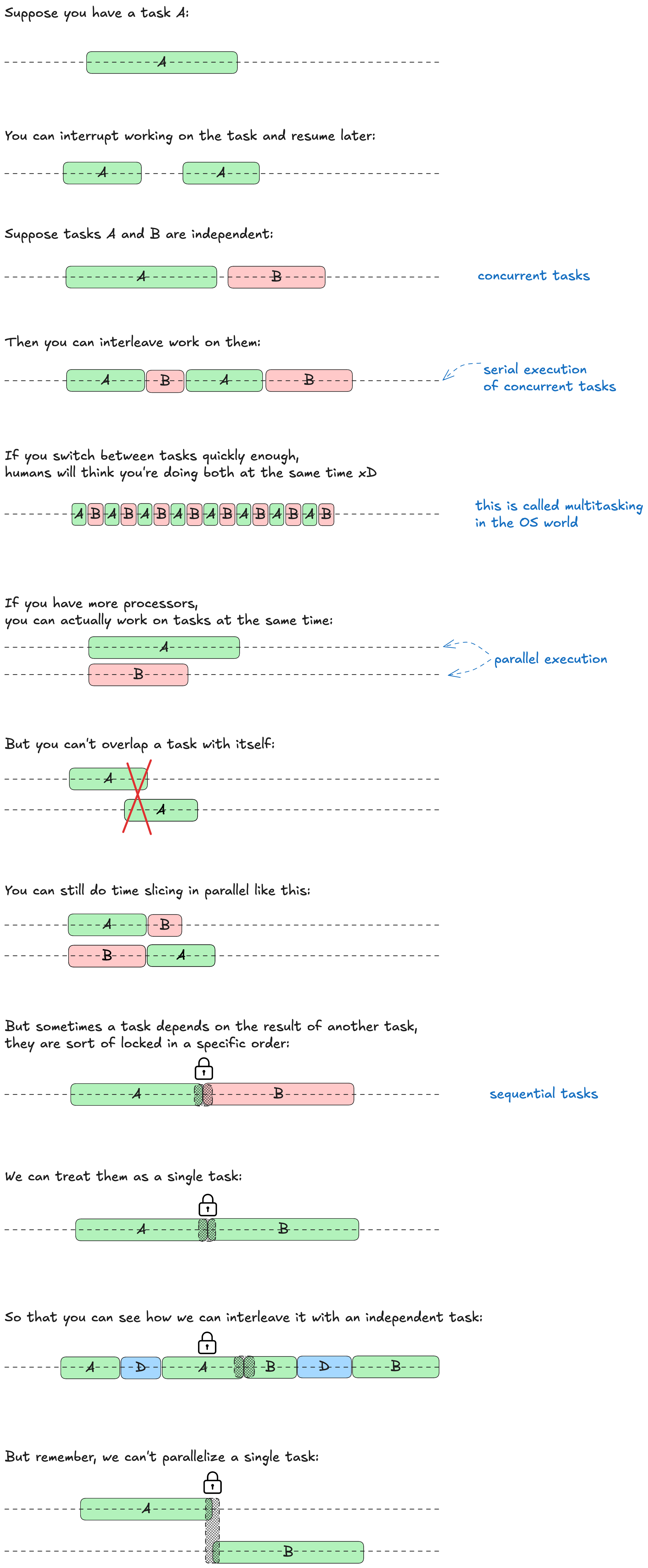

I like the time slicing diagrams, so I tried try to adapt them to our new definition of concurrency. In this tutorial, two tasks are sequential if they are locked to each other, and concurrent otherwise. Parallelism is self-explanatory.

Why are there so many definitions?

One reason why the misleading definitions and analogies exist is that concurrency is implemented in different ways depending on the level. For example, in the world of Operating Systems, concurrency is represented by threads and time slicing. In the software engineering world, it is represented by coroutines. Distributed systems need study concurrency more in-depth, so they will find the correct definition very useful though.

Another reason is that an accurate and general definition of concurrency (like the one from The Glossary) might seem a bit too abstract for some people. They might prefer a simple but imprecise analogy because it gives them that feeling of intuitive understanding.

However, I believe that such hand-wavy definitions can only give you a partial understanding at best, and a completely wrong understanding at worst, so they are not good enough by themselves (they can still be used as stepping stones). Any programmer who is serious about his craft will not stop at flimsy analogies but will instead keep digging, progressing from simpler definitions to more rigorous ones, until he finds the single source of truth and is able to grasp it and build a correct understanding of the topic.

The Glossary contains the best definitions I've found so far, but as the author points out, it is just an "informal top-level overview", so we have to keep digging.

Bibliography

Van Roy, Peter (2012). Programming Paradigms for Dummies: What Every Programmer Should Know.

slikts (2025). Concurrency Glossary: Informal definitions of terms used in concurrency modeling.

Footnotes:

After all, if a thing appears to be a certain way, then it either truly is that way, or it is not that way, but we perceive it to be that way (because of an illusion or something), thus "appearing to be a certain way" is a proper superset of "truly being a certain way". QED.

Indeed, in the article linked in The Glossary, "Programming Paradigms for Dummies" by Peter Van Roy (which is great and you must read! 3), "independence" is used as a synonym for "concurrency".

In fact, the author wrote a book titled "Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming" which from a quick glance is very based in the same way as SICP. Looks like it puts an end to the dumb wars of paradigms a-la "FP vs. OOP" by seeing the use-case for each – "More is not better (or worse) than less, just different" (but it agrees that FP should be the default, which makes me fall in love). Will definitely give it a read.

The opposite of well-defined interaction is probably unintended interaction (e.g. when the programmer didn't expect that two threads will be writing to the same file).

This could be solved if instead of autographs, for example, the problem were to rank the kids by height. If we admit that the processor (the table) is simply assigning a number to each kid and then incrementing it, then the order in which the kids came up to the table would indeed matter (they would have to be sorted by height), and we could say they are sequential. But this doesn't sound like a very intuitive analogy.